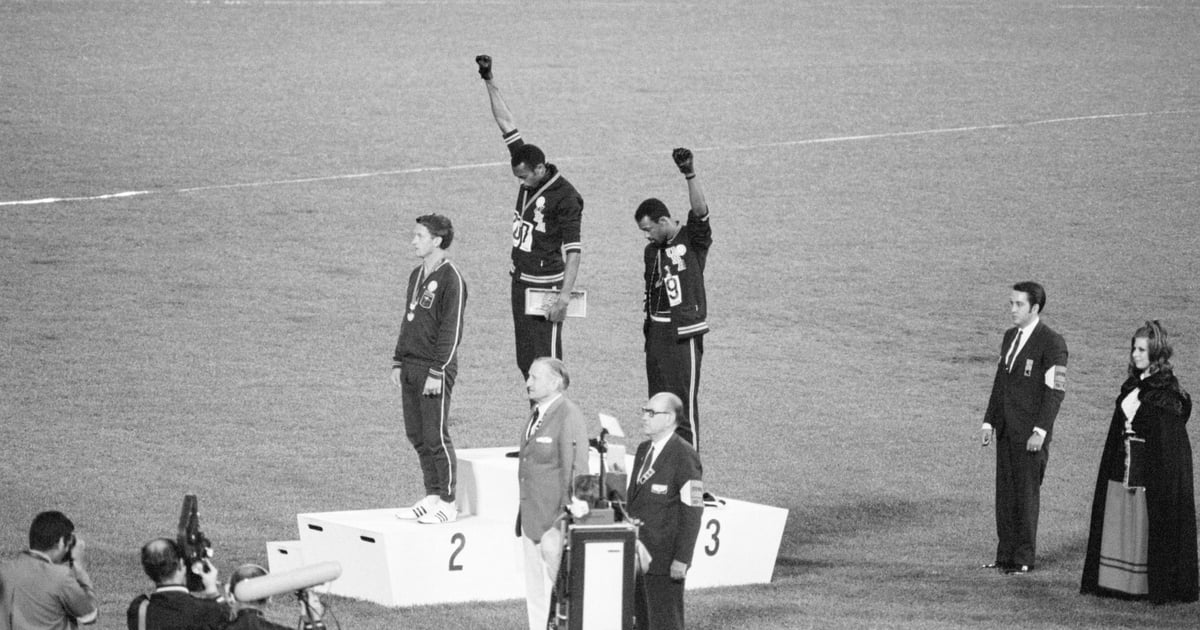

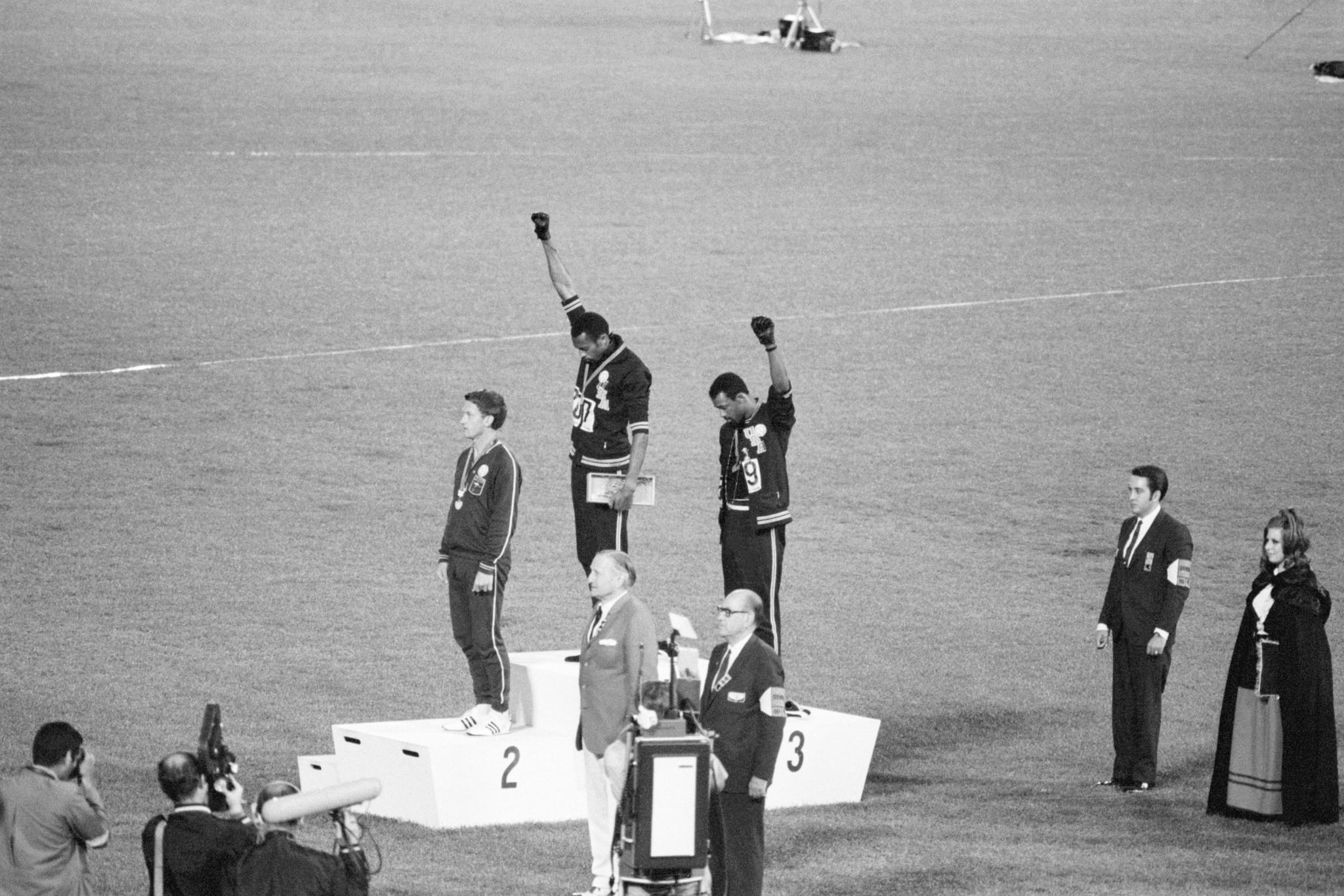

Photo: American sprinters Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos (right) demonstrating during the men’s 200-meter medal ceremony at the 1968 Olympic Games.

The US Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) announced on Dec. 10 that it will no longer penalize athletes who choose to take part in peaceful protests. The committee is doing so in support of the Team USA Council on Racial and Social Justice, which released its recommendations for amending longstanding policies put in place by governing bodies International Olympic Committee (IOC) and International Paralympic Committee (IPC) — the policies were evaluated by the council’s Protests and Demonstrations Steering Committee formed this September.

Rule 50 in the IOC Olympic Charter states, “No kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” IPC Handbook Section 2.2 features similar language. In January of 2020, the IOC Athletes’ Commission clarified that though the IOC is supportive of freedom of expression, examples of prohibited acts include: “Gestures of a political nature, like a hand gesture or kneeling.” It also specified the designated areas where this rule applies: on the field of play, in the Olympic Village, at Olympic medal ceremonies, and during the opening and closing ceremonies.

One athlete who was reprimanded for protesting? Gwen Berry. At the 2019 Pan American Games, she raised a fist and bowed her head on the podium when accepting a gold medal for the hammer throw. She, along with fencer Race Imboden, who won gold in his sport at the Pan Am Games that year as well and took a knee, demonstrated separately but for the same cause: racial and social justice. The USOPC put them both on a 12-month probation.

Five decades prior was the iconic protest in 1968 from American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos. Atop the Olympic podium for the men’s 200-meter medal ceremony in Mexico City, each raised a fist while the national anthem played. Their demonstration is referred to as the Black Power salute, though Smith wrote in his autobiography that the action was more than that; he said it was a demonstration for human rights. What was then known simply as the US Olympic Committee wanted to issue a warning, but after pressure from the IOC, the men were expelled from the Games.

“The silencing of athletes during the Games is in stark contrast to the importance of recognizing participants in the Games as humans first and athletes second.”

Fast forward to 2020, Team USA Council on Racial and Social Justice states in its recommendations: “The silencing of athletes during the Games is in stark contrast to the importance of recognizing participants in the Games as humans first and athletes second. Prohibiting athletes to freely express their views during the Games, particularly those from historically underrepresented and minoritized groups, contributes to the dehumanization of athletes that is at odds with key Olympic and Paralympic values.”

The Council urges the IOC to recognize that protests in the name of human rights and social justice are not “divisive disruptions,” as the IOC has formerly called them. Additionally, the council writes, “We want to make unmistakably clear that human rights are not political; yet, they have been politicized both in the U.S. and globally to perpetuate the wrongful and dehumanizing myth of sport as an inherently neutral domain.”

By trying to keep sports “neutral,” this, the council argues, targets “historically marginalized and minoritized populations within the Olympic and Paralympic community, most notably Black athletes and athletes of color, who have competed and excelled in Olympic and Paralympic Games against the backdrop of various social injustices and turmoil.”

Taking into account the demonstrations we’ve seen from professional athletes across sports specifically in 2020, it’s unknown what any such protests at the Olympic Games will bring. As track and field Olympian Moushaumi Robinson wrote in a published letter on behalf of the Team USA Council on Racial and Social Justice, the IOC and IPC have ultimate authority “within the Games environments.”

The New York Times does state the the IOC “has historically called on individual organizing committees to dole out punishments for violations.” And, given that the USOPC is saying it will not penalize peaceful demonstrations, that is a step forward after a history of doing . . . well . . . the opposite.

“The USOPC will not sanction Team USA athletes for respectfully demonstrating in support of racial and social justice for all human beings,” a statement reads. USOPC CEO Sarah Hirshland added that the committee “values the voices of Team USA athletes” as a “positive force for change.” In a letter addressed to Team USA members, she said that the USOPC will continue to work with the IOC and IPC as they “consider amendments” to their longstanding rules on protests.

Since they are actively accepting feedback from athletes around the world on the state of these rules, we reportedly can’t expect any final decisions until early next year. And, though the IOC did not initially mention a timeline, the IPC said its Athletes’ Council would present final recommendations in late February.